The Victoria Cross

The History Of The Victoria Cross

In 1854, after 40 years of peace, Britain found itself fighting a major war against Russia. From the early days of the Crimean War, stories abounded of the outstanding bravery of British sailors and soldiers in the most appalling conditions. Their heroics were performed despite the lack of adequate winter clothing and other provisions to protect them from the harsh Russian winter. This was the first war covered by modern-style war reporters and William Howard Russell, of The Times, filed a succession of vivid reports. His stories highlighted the lack of proper equipment and the ravages of cholera and typhoid fever, two diseases that claimed 20,000 lives compared to the 3,400 killed in battle.

There was a general clamour that something needed to be done to recognise the efforts of rank and file British servicemen who were risking their lives thousands of miles from home. Until the Crimean War, officers – usually of the rank of major and above – were given the junior grade of the Order of the Bath for acts of bravery. Yet there was no such equivalent medal for junior officers, Non-Commissioned Officers (NCOs), or ordinary soldiers or sailors. There was a growing feeling that a new award was needed to recognise incidents of gallantry that were unconnected with a man’s lengthy or meritorious service.

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, her consort, were enthusiastic about addressing the problem, particularly as the enemy, the Russians, already had their awards for gallantry that ignored rank. By 1855, the momentum for a new gallantry award was such that Queen Victoria was choosing the design. She favoured a Maltese cross ensigned with a royal crest and a scroll inscribed “For Valour”. The Government had wanted the cross inscribed “For the Brave”, but the Queen was concerned that this would imply that non-recipients were not brave.

The VC was founded by a Royal Warrant issued on January 29 1856. The warrant announced the creation of a single decoration available to the Army and Royal Navy which was intended to reward “individual instances of merit and valour” and which “we are desirous should be highly prized and eagerly sought after”. The warrant laid down fifteen “rules and ordinances”. Essentially, however, the award was intended for extreme bravery in the presence of the enemy. It was also decided that the cross should be made from metal of little intrinsic value. It was intended that it should be bronze and cast from metal melted down from two cannon supposedly captured from the Russians at Sebastopol in the Crimean War.

It was more than a year after the Royal Warrant was signed that the first awards of the VC were published in The London Gazette – on February 24 1857. The Queen had told her senior ministers that she wished to bestow as many of the awards as possible. So in June 1857 the Queen invested 62 of the 111 Crimean recipients at a ceremony in Hyde Park in front of more than 4,000 troops and 12,000 spectators.

Over the years, there have been several significant amendments to the rules relating to the VC. The first changes to the regulations came little more than a year after the announcement that the VC had been awarded for the first time. A Royal Warrant of August 10 1858 extended the VC to “non-military persons”. Under this new clause, four civilians received the VC for their voluntary service in the Indian Mutiny. Many further changes followed but the core principles of the VC remain to this day.

The Second Anglo-Boer War, fought in Africa between 1899 and 1902, saw the first really serious dispute over the award of a VC. The Hon Frederick Roberts was the son of Field Marshal Earl Roberts, who had been awarded the VC for an act of bravery in 1858 during the Indian Mutiny. The Hon Frederick Roberts was 27 years old when he was seriously wounded on 15 December 1899, during heroics at the Battle of Colenso. He died from his wounds just over 24 hours later. There was surprise, therefore, when his VC was “gazetted” on February 2 1900, and he was given a posthumous medal. There was some anger that he had been treated as a special case apparently because of the influence of his father.

The families of other potential recipients of posthumous VCs began to ask why their relatives could not be given a posthumous VC even though they had died many years earlier. In The London Gazette of August 8 1902, Edward VII approved the award of six posthumous VCs all relating to incidents during the Boer War. Although the families of the dead recipients were satisfied with this outcome, the families of men who had died in six similar cases which had been “gazetted” between 1859 and 1897 remained unhappy that their relatives had still not been awarded the VC. The King resisted this pressure for five years but finally, in 1907, he relented and the crosses were “gazetted” and delivered to the families of the dead men. The controversy surrounding Roberts’ decoration meant the precedent for posthumous awards of the VC had been established once and for all and in 1920 the rules were formally re-written.

Since its institution, the VC has been made and supplied by Messrs Hancocks (now Hancocks & Co), the London jewellers. There have been countless attempts to produce fakes and copies. Hancocks, however, prides itself on being able to tell a genuine VC from a fake under close examination, including testing the metal.

There are endless fascinating facts and figures surrounding the VC. The cross is 1.375 inches wide and weighs 0.87 ounces, together with the suspender bar and V-shaped link. The face of the bar is embossed with laurel leaves, while the recipient’s details are engraved on the reverse. The date of the act of bravery is engraved in the centre of the circle on the reverse of the cross. The details given on the suspender bar sometimes vary but the norm is to provide the rank, name and unit of the recipient.

To date (and not including separate awards that can now be made from Australia, New Zealand and Canada), 1,358 VCs have been awarded for bravery to 1,355 men. The awards include three Bars – the equivalent of a second VC – and a special award to the American Unknown Warrior. The youngest recipient of the VC was just 15 years old and three months, the oldest was two months short of his 62nd birthday.

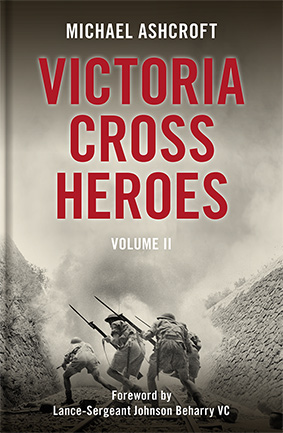

Victoria Cross Heroes Volume II

Published by Biteback Publishing, the book is available from November 8 2016. It has two principle aims: to champion acts of great bravery and to raise money for charity. All author’s royalties are being donated to military charities.

Buy the book